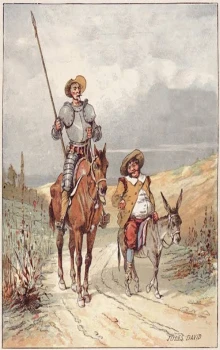

OF HOW DON QUIXOTE FELL SICK, AND OF THE WILL HE MADE, AND HOW HE DIED

As nothing that is man's can last for ever, but all tends ever downwards

from its beginning to its end, and above all man's life, and as Don Quixote's

enjoyed no special dispensation from heaven to stay its course, its end and

close came when he least looked for it. For-whether it was of the dejection

the thought of his defeat produced, or of heaven's will that so ordered it—a

fever settled upon him and kept him in his bed for six days, during which he

was often visited by his friends the curate, the bachelor, and the barber,

while his good squire Sancho Panza never quitted his bedside. They, per-

suaded that it was grief at finding himself vanquished, and the object of his

heart, the liberation and disenchantment of Dulcinea, unattained, that kept

him in this state, strove by all the means in their power to cheer him up; the

bachelor bidding him take heart and get up to begin his pastoral life, for

which he himself, he said, had already composed an eclogue that would

take the shine out of all Sannazaro had ever written, and had bought with

his own money two famous dogs to guard the flock, one called Barcino and

the other Butron, which a herdsman of Quintanar had sold him.

But for all this Don Quixote could not shake off his sadness. His friends

called in the doctor, who felt his pulse and was not very well satisfied with

it, and said that in any case it would be well for him to attend to the health

of his soul, as that of his body was in a bad way. Don Quixote heard this

calmly; but not so his housekeeper, his niece, and his squire, who fell weep-

ing bitterly, as if they had him lying dead before them. The doctor's opinion

was that melancholy and depression were bringing him to his end. Don

Quixote begged them to leave him to himself, as he had a wish to sleep a

little. They obeyed, and he slept at one stretch, as the saying is, more than

six hours, so that the housekeeper and niece thought he was going to sleep

for ever. But at the end of that time he woke up, and in a loud voice ex-

claimed, "Blessed be Almighty God, who has shown me such goodness. In

truth his mercies are boundless, and the sins of men can neither limit them

nor keep them back!"

The niece listened with attention to her uncle's words, and they struck her

as more coherent than what usually fell from him, at least during his illness,

so she asked, "What are you saying, senor? Has anything strange occurred?

What mercies or what sins of men are you talking of?"

"The mercies, niece," said Don Quixote, "are those that God has this mo-

ment shown me, and with him, as I said, my sins are no impediment to

them. My reason is now free and clear, rid of the dark shadows of ignorance

that my unhappy constant study of those detestable books of chivalry cast

over it. Now I see through their absurdities and deceptions, and it only

grieves me that this destruction of my illusions has come so late that it

leaves me no time to make some amends by reading other books that might

be a light to my soul. Niece, I feel myself at the point of death, and I would

fain meet it in such a way as to show that my life has not been so ill that I

should leave behind me the name of a madman; for though I have been one,

I would not that the fact should be made plainer at my death. Call in to me,

my dear, my good friends the curate, the bachelor Samson Carrasco, and

Master Nicholas the barber, for I wish to confess and make my will." But

his niece was saved the trouble by the entrance of the three. The instant Don

Quixote saw them he exclaimed, "Good news for you, good sirs, that I am

no longer Don Quixote of La Mancha, but Alonso Quixano, whose way of

life won for him the name of Good. Now am I the enemy of Amadis of Gaul

and of the whole countless troop of his descendants; odious to me now are

all the profane stories of knight-errantry; now I perceive my folly, and the

peril into which reading them brought me; now, by God's mercy schooled

into my right senses, I loathe them."

When the three heard him speak in this way, they had no doubt whatever

that some new craze had taken possession of him; and said Samson, "What?

Senor Don Quixote! Now that we have intelligence of the lady Dulcinea be-

ing disenchanted, are you taking this line; now, just as we are on the point

of becoming shepherds, to pass our lives singing, like princes, are you

thinking of turning hermit? Hush, for heaven's sake, be rational and let's

have no more nonsense."

"All that nonsense," said Don Quixote, "that until now has been a reality

to my hurt, my death will, with heaven's help, turn to my good. I feel, sirs,

that I am rapidly drawing near death; a truce to jesting; let me have a con-

fessor to confess me, and a notary to make my will; for in extremities like

this, man must not trifle with his soul; and while the curate is confessing me

let some one, I beg, go for the notary."

They looked at one another, wondering at Don Quixote's words; but,

though uncertain, they were inclined to believe him, and one of the signs by

which they came to the conclusion he was dying was this so sudden and

complete return to his senses after having been mad; for to the words al-

ready quoted he added much more, so well expressed, so devout, and so ra-

tional, as to banish all doubt and convince them that he was sound of mind.

The curate turned them all out, and left alone with him confessed him. The

bachelor went for the notary and returned shortly afterwards with him and

with Sancho, who, having already learned from the bachelor the condition

his master was in, and finding the housekeeper and niece weeping, began to

blubber and shed tears.

The confession over, the curate came out saying, "Alonso Quixano the

Good is indeed dying, and is indeed in his right mind; we may now go in to

him while he makes his will."

This news gave a tremendous impulse to the brimming eyes of the house-

keeper, niece, and Sancho Panza his good squire, making the tears burst

from their eyes and a host of sighs from their hearts; for of a truth, as has

been said more than once, whether as plain Alonso Quixano the Good, or as

Don Quixote of La Mancha, Don Quixote was always of a gentle disposi-

tion and kindly in all his ways, and hence he was beloved, not only by those

of his own house, but by all who knew him.

The notary came in with the rest, and as soon as the preamble of the had

been set out and Don Quixote had commended his soul to God with all the

devout formalities that are usual, coming to the bequests, he said, "Item, it

is my will that, touching certain moneys in the hands of Sancho Panza

(whom in my madness I made my squire), inasmuch as between him and

me there have been certain accounts and debits and credits, no claim be

made against him, nor any account demanded of him in respect of them; but

that if anything remain over and above, after he has paid himself what I owe

him, the balance, which will be but little, shall be his, and much good may

it do him; and if, as when I was mad I had a share in giving him the govern-

ment of an island, so, now that I am in my senses, I could give him that of a

kingdom, it should be his, for the simplicity of his character and the fidelity

of his conduct deserve it." And then, turning to Sancho, he said, "Forgive

me, my friend, that I led thee to seem as mad as myself, making thee fall

into the same error I myself fell into, that there were and still are knights-

errant in the world."

"Ah!" said Sancho weeping, "don't die, master, but take my advice and

live many years; for the foolishest thing a man can do in this life is to let

himself die without rhyme or reason, without anybody killing him, or any

hands but melancholy's making an end of him. Come, don't be lazy, but get

up from your bed and let us take to the fields in shepherd's trim as we

agreed. Perhaps behind some bush we shall find the lady Dulcinea disen-

chanted, as fine as fine can be. If it be that you are dying of vexation at hav-

ing been vanquished, lay the blame on me, and say you were overthrown

because I had girthed Rocinante badly; besides you must have seen in your

books of chivalry that it is a common thing for knights to upset one another,

and for him who is conquered to-day to be conqueror tomorrow."

"Very true," said Samson, "and good Sancho Panza's view of these cases

is quite right."

"Sirs, not so fast," said Don Quixote, "'in last year's nests there are no

birds this year.' I was mad, now I am in my senses; I was Don Quixote of

La Mancha, I am now, as I said, Alonso Quixano the Good; and may my

repentance and sincerity restore me to the esteem you used to have for me;

and now let Master Notary proceed.

"Item, I leave all my property absolutely to Antonia Quixana my niece,

here present, after all has been deducted from the most available portion of

it that may be required to satisfy the bequests I have made. And the first dis-

bursement I desire to be made is the payment of the wages I owe for the

time my housekeeper has served me, with twenty ducats, over and above,

for a gown. The curate and the bachelor Samson Carrasco, now present, I

appoint my executors.

"Item, it is my wish that if Antonia Quixana, my niece, desires to marry,

she shall marry a man of whom it shall be first of all ascertained by infor-

mation taken that he does not know what books of chivalry are; and if it

should be proved that he does, and if, in spite of this, my niece insists upon

marrying him, and does marry him, then that she shall forfeit the whole of

what I have left her, which my executors shall devote to works of charity as

they please.

"Item, I entreat the aforesaid gentlemen my executors, that, if any happy

chance should lead them to discover the author who is said to have written a

history now going about under the title of 'Second Part of the Achievements

of Don Quixote of La Mancha,' they beg of him on my behalf as earnestly

as they can to forgive me for having been, without intending it, the cause of

his writing so many and such monstrous absurdities as he has written in it;

for I am leaving the world with a feeling of compunction at having pro-

voked him to write them."

With this he closed his will, and a faintness coming over him he stretched

himself out at full length on the bed. All were in a flutter and made haste to

relieve him, and during the three days he lived after that on which he made

his will he fainted away very often. The house was all in confusion; but still

the niece ate and the housekeeper drank and Sancho Panza enjoyed himself;

for inheriting property wipes out or softens down in the heir the feeling of

grief the dead man might be expected to leave behind him.

At last Don Quixote's end came, after he had received all the sacraments,

and had in full and forcible terms expressed his detestation of books of

chivalry. The notary was there at the time, and he said that in no book of

chivalry had he ever read of any knight-errant dying in his bed so calmly

and so like a Christian as Don Quixote, who amid the tears and lamenta-

tions of all present yielded up his spirit, that is to say died. On perceiving it

the curate begged the notary to bear witness that Alonso Quixano the Good,

commonly called Don Quixote of La Mancha, had passed away from this

present life, and died naturally; and said he desired this testimony in order

to remove the possibility of any other author save Cide Hamete Benengeli

bringing him to life again falsely and making interminable stories out of his

achievements.

Such was the end of the Ingenious Gentleman of La Mancha, whose vil-

lage Cide Hamete would not indicate precisely, in order to leave all the

towns and villages of La Mancha to contend among themselves for the right

to adopt him and claim him as a son, as the seven cities of Greece contend-

ed for Homer. The lamentations of Sancho and the niece and housekeeper

are omitted here, as well as the new epitaphs upon his tomb; Samson Car-

rasco, however, put the following lines:

{verse

A doughty gentleman lies here;

A stranger all his life to fear;

Nor in his death could Death prevail,

In that last hour, to make him quail.

He for the world but little cared;

And at his feats the world was scared;

A crazy man his life he passed,

But in his senses died at last.

{verse

And said most sage Cide Hamete to his pen, "Rest here, hung up by this

brass wire, upon this shelf, O my pen, whether of skilful make or clumsy

cut I know not; here shalt thou remain long ages hence, unless presumptu-

ous or malignant story-tellers take thee down to profane thee. But ere they

touch thee warn them, and, as best thou canst, say to them:

{verse

Hold off! ye weaklings; hold your hands!

Adventure it let none,

For this emprise, my lord the king,

Was meant for me alone.

{verse

For me alone was Don Quixote born, and I for him; it was his to act,

mine to write; we two together make but one, notwithstanding and in spite

of that pretended Tordesillesque writer who has ventured or would venture

with his great, coarse, ill-trimmed ostrich quill to write the achievements of

my valiant knight;—no burden for his shoulders, nor subject for his frozen

wit: whom, if perchance thou shouldst come to know him, thou shalt warn

to leave at rest where they lie the weary mouldering bones of Don Quixote,

and not to attempt to carry him off, in opposition to all the privileges of

death, to Old Castile, making him rise from the grave where in reality and

truth he lies stretched at full length, powerless to make any third expedition

or new sally; for the two that he has already made, so much to the enjoy-

ment and approval of everybody to whom they have become known, in this

as well as in foreign countries, are quite sufficient for the purpose of turning

into ridicule the whole of those made by the whole set of the knights-errant;

and so doing shalt thou discharge thy Christian calling, giving good counsel

to one that bears ill-will to thee. And I shall remain satisfied, and proud to

have been the first who has ever enjoyed the fruit of his writings as fully as

he could desire; for my desire has been no other than to deliver over to the

detestation of mankind the false and foolish tales of the books of chivalry,

which, thanks to that of my true Don Quixote, are even now tottering, and

doubtless doomed to fall for ever. Farewell."

This book has been downloaded from www.aliceandbooks.com. You can

find many more public domain books in our website