Riding inside the dimly lit cargo hold of the armored truck was like being transported

inside a cell for solitary confinement. Langdon fought the all too familiar anxiety that

haunted him in confined spaces. Vernet said he would take us a safe distance out of the

city. Where? How far?

Langdon's legs had gotten stiff from sitting cross-legged on the metal floor, and he

shifted his position, wincing to feel the blood pouring back into his lower body. In his

arms, he still clutched the bizarre treasure they had extricated from the bank.

“I think we're on the highway now,” Sophie whispered.

Langdon sensed the same thing. The truck, after an unnerving pause atop the bank

ramp, had moved on, snaking left and right for a minute or two, and was now

accelerating to what felt like top speed. Beneath them, the bulletproof tires hummed on

smooth pavement. Forcing his attention to the rosewood box in his arms, Langdon laid

the precious bundle on the floor, unwrapped his jacket, and extracted the box, pulling it

toward him. Sophie shifted her position so they were sitting side by side. Langdon

suddenly felt like they were two kids huddled over a Christmas present.

In contrast to the warm colors of the rosewood box, the inlaid rose had been crafted of

a pale wood, probably ash, which shone clearly in the dim light. The Rose. Entire armies

and religions had been built on this symbol, as had secret societies. The Rosicrucians.

The Knights of the Rosy Cross.

“Go ahead,” Sophie said. “Open it.”

Langdon took a deep breath. Reaching for the lid, he stole one more admiring glance at

the intricate woodwork and then, unhooking the clasp, he opened the lid, revealing the

object within.

Langdon had harbored several fantasies about what they might find inside this box, but

clearly he had been wrong on every account. Nestled snugly inside the box's heavily

padded interior of crimson silk lay an object Langdon could not even begin to

comprehend.

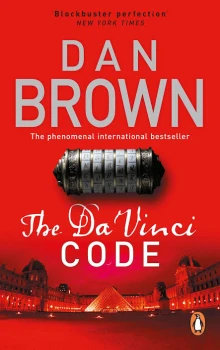

Crafted of polished white marble, it was a stone cylinder approximately the dimensions

of a tennis ball can. More complicated than a simple column of stone, however, the

cylinder appeared to have been assembled in many pieces. Six doughnut-sized disks of

marble had been stacked and affixed to one another within a delicate brass framework. It

looked like some kind of tubular, multiwheeled kaleidoscope. Each end of the cylinder

was affixed with an end cap, also marble, making it impossible to see inside. Having

heard liquid within, Langdon assumed the cylinder was hollow.

As mystifying as the construction of the cylinder was, however, it was the engravings

around the tube's circumference that drew Langdon's primary focus. Each of the six disks

had been carefully carved with the same unlikely series of letters—the entire alphabet.

The lettered cylinder reminded Langdon of one of his childhood toys—a rod threaded

with lettered tumblers that could be rotated to spell different words.

“Amazing, isn't it?” Sophie whispered.

Langdon glanced up. “I don't know. What the hell is it?”

Now there was a glint in Sophie's eye. “My grandfather used to craft these as a hobby.

They were invented by Leonardo da Vinci.”

Even in the diffuse light, Sophie could see Langdon's surprise.

“Da Vinci?” he muttered, looking again at the canister.

“Yes. It's called a cryptex. According to my grandfather, the blueprints come from one

of Da Vinci's secret diaries.”

“What is it for?”

Considering tonight's events, Sophie knew the answer might have some interesting

implications. “It's a vault,” she said. “For storing secret information.”

Langdon's eyes widened further.

Sophie explained that creating models of Da Vinci's inventions was one of her

grandfather's best-loved hobbies. A talented craftsman who spent hours in his wood and

metal shop, Jacques Saunière enjoyed imitating master craftsmen—Fabergé, assorted

cloisonné artisans, and the less artistic, but far more practical, Leonardo da Vinci.

Even a cursory glance through Da Vinci's journals revealed why the luminary was as

notorious for his lack of follow-through as he was famous for his brilliance. Da Vinci

had drawn up blueprints for hundreds of inventions he had never built. One of Jacques

Saunière's favorite pastimes was bringing Da Vinci's more obscure brainstorms to life—

timepieces, water pumps, cryptexes, and even a fully articulated model of a medieval

French knight, which now stood proudly on the desk in his office. Designed by Da Vinci

in 1495 as an outgrowth of his earliest anatomy and kinesiology studies, the internal

mechanism of the robot knight possessed accurate joints and tendons, and was designed

to sit up, wave its arms, and move its head via a flexible neck while opening and closing

an anatomically correct jaw. This armor-clad knight, Sophie had always believed, was the

most beautiful object her grandfather had ever built . . . that was, until she had seen the

cryptex in this rosewood box.

“He made me one of these when I was little,” Sophie said. “But I've never seen one so

ornate and large.”

Langdon's eyes had never left the box. “I've never heard of a cryptex.”

Sophie was not surprised. Most of Leonardo's unbuilt inventions had never been

studied or even named. The term cryptex possibly had been her grandfather's creation, an

apt title for this device that used the science of cryptology to protect information written

on the contained scroll or codex.

Da Vinci had been a cryptology pioneer, Sophie knew, although he was seldom given

credit. Sophie's university instructors, while presenting computer encryption methods for

securing data, praised modern cryptologists like Zimmerman and Schneier but failed to

mention that it was Leonardo who had invented one of the first rudimentary forms of

public key encryption centuries ago. Sophie's grandfather, of course, had been the one to

tell her all about that.

As their armored truck roared down the highway, Sophie explained to Langdon that

the cryptex had been Da Vinci's solution to the dilemma of sending secure messages over

long distances. In an era without telephones or e-mail, anyone wanting to convey private

information to someone far away had no option but to write it down and then trust a

messenger to carry the letter. Unfortunately, if a messenger suspected the letter might

contain valuable information, he could make far more money selling the information to

adversaries than he could delivering the letter properly.

Many great minds in history had invented cryptologic solutions to the challenge of data

protection: Julius Caesar devised a code-writing scheme called the Caesar Box; Mary,

Queen of Scots created a transposition cipher and sent secret communiqués from prison;

and the brilliant Arab scientist Abu Yusuf Ismail al-Kindi protected his secrets with an

ingeniously conceived polyalphabetic substitution cipher.

Da Vinci, however, eschewed mathematics and cryptology for a mechanical solution.

The cryptex. A portable container that could safeguard letters, maps, diagrams, anything

at all. Once information was sealed inside the cryptex, only the individual with the proper

password could access it.

“We require a password,” Sophie said, pointing out the lettered dials. “A cryptex

works much like a bicycle's combination lock. If you align the dials in the proper

position, the lock slides open. This cryptex has five lettered dials. When you rotate them

to their proper sequence, the tumblers inside align, and the entire cylinder slides apart.”

“And inside?”

“Once the cylinder slides apart, you have access to a hollow central compartment,

which can hold a scroll of paper on which is the information you want to keep private.”

Langdon looked incredulous. “And you say your grandfather built these for you when

you were younger?”

“Some smaller ones, yes. A couple times for my birthday, he gave me a cryptex and

told me a riddle. The answer to the riddle was the password to the cryptex, and once I

figured it out, I could open it up and find my birthday card.”

“A lot of work for a card.”

“No, the cards always contained another riddle or clue. My grandfather loved creating

elaborate treasure hunts around our house, a string of clues that eventually led to my real

gift. Each treasure hunt was a test of character and merit, to ensure I earned my rewards.

And the tests were never simple.”

Langdon eyed the device again, still looking skeptical. “But why not just pry it apart?

Or smash it? The metal looks delicate, and marble is a soft rock.”

Sophie smiled. “Because Da Vinci is too smart for that. He designed the cryptex so that

if you try to force it open in any way, the information self-destructs. Watch.” Sophie

reached into the box and carefully lifted out the cylinder. “Any information to be inserted

is first written on a papyrus scroll.”

“Not vellum?”

Sophie shook her head. “Papyrus. I know sheep's vellum was more durable and more

common in those days, but it had to be papyrus. The thinner the better.”

“Okay.”

“Before the papyrus was inserted into the cryptex's compartment, it was rolled around

a delicate glass vial.” She tipped the cryptex, and the liquid inside gurgled. “A vial of

liquid.”

“Liquid what?”

Sophie smiled. “Vinegar.”

Langdon hesitated a moment and then began nodding. “Brilliant.”

Vinegar and papyrus, Sophie thought. If someone attempted to force open the cryptex,

the glass vial would break, and the vinegar would quickly dissolve the papyrus. By the

time anyone extracted the secret message, it would be a glob of meaningless pulp.

“As you can see,” Sophie told him, “the only way to access the information inside is to

know the proper five-letter password. And with five dials, each with twenty-six letters,

that's twenty-six to the fifth power.” She quickly estimated the permutations.

“Approximately twelve million possibilities.”

“If you say so,” Langdon said, looking like he had approximately twelve million

questions running through his head. “What information do you think is inside?”

“Whatever it is, my grandfather obviously wanted very badly to keep it secret.” She

paused, closing the box lid and eyeing the five-petal Rose inlaid on it. Something was

bothering her. “Did you say earlier that the Rose is a symbol for the Grail?”

“Exactly. In Priory symbolism, the Rose and the Grail are synonymous.”

Sophie furrowed her brow. “That's strange, because my grandfather always told me the

Rose meant secrecy. He used to hang a rose on his office door at home when he was

having a confidential phone call and didn't want me to disturb him. He encouraged me to

do the same.” Sweetie, her grandfather said, rather than lock each other out, we can each

hang a rose—la fleur des secrets—on our door when we need privacy. This way we learn

to respect and trust each other. Hanging a rose is an ancient Roman custom.

“Sub rosa,” Langdon said. “The Romans hung a rose over meetings to indicate the

meeting was confidential. Attendees understood that whatever was said under the rose—

or sub rosa—had to remain a secret.”

Langdon quickly explained that the Rose's overtone of secrecy was not the only reason

the Priory used it as a symbol for the Grail. Rosa rugosa, one of the oldest species of

rose, had five petals and pentagonal symmetry, just like the guiding star of Venus, giving

the Rose strong iconographic ties to womanhood. In addition, the Rose had close ties to

the concept of “true direction” and navigating one's way. The Compass Rose helped

travelers navigate, as did Rose Lines, the longitudinal lines on maps. For this reason, the

Rose was a symbol that spoke of the Grail on many levels—secrecy, womanhood, and

guidance—the feminine chalice and guiding star that led to secret truth.

As Langdon finished his explanation, his expression seemed to tighten suddenly.

“Robert? Are you okay?”

His eyes were riveted to the rosewood box. “Sub . . . rosa,” he choked, a fearful

bewilderment sweeping across his face. “It can't be.”

“What?”

Langdon slowly raised his eyes. “Under the sign of the Rose,” he whispered. “This

cryptex . . . I think I know what it is.”